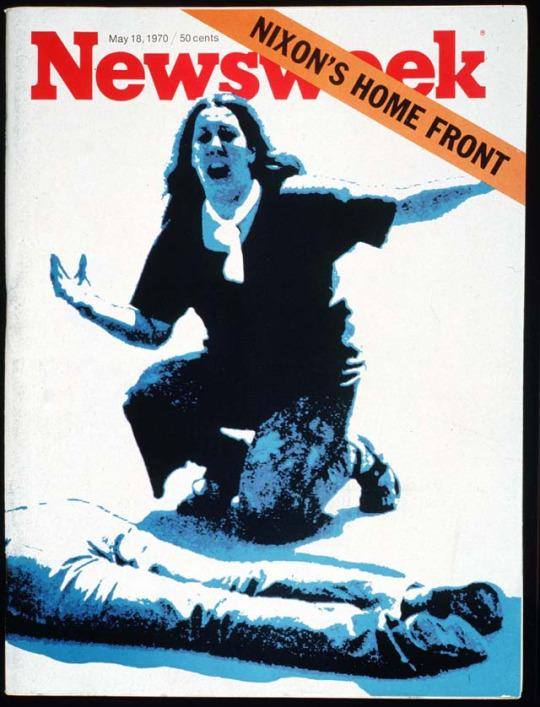

Four dead in Ohio. And a searing image: A young man face-down at Kent State while a young woman screams over his body.

Fifty years ago today that sequence of events began. Dominoes started falling on the home front, just like the ones in Asia. As they fell, they dragged America from the exuberance of Woodstock into the self-doubt of Watergate.

The chain reaction began in Ohio on May 4, 1970. Students protesting President Richard Nixon’s April 30 invasion of Cambodia marched on the campus of Kent State University.

National Guard forces fired on them.

Four died.

The nation came unglued so fast the shock rippled worldwide. Tensions that had simmered for years now boiled over into something savage, deadly, and terrifying to everyone who watched, and not just to the students.

It became the point when President Nixon himself began to unravel into the paranoia that brought him low four years later.

Glimpses of his instability came to view five days after the Kent State killings when the President made an unannounced visit to the Lincoln Memorial. Seeming almost bereft, the President pressed his rambling arguments on bewildered student protesters camped there at night. .

The larger national reaction to Kent State had a similar cast. It became one of the sudden historical shifts that can be seen time and again in American history, where one thing flips into its opposite.

In 1970, overweening optimism flipped into obsessive fear about what was happening to the nation. Our own institutions, which seemed to work so well until then, were tearing themselves to pieces as we watched on television.

The 1960s were dying before our eyes.

The idealism of that decade had long since developed a utopian and sometimes fantastical fervor. But it mostly had been good-natured until Kent State.

America still believed in utopia at this point. Heaven on earth was possible, we thought. And we had the money to make it happen.

As if money can buy heaven.

Parents of the day indulged their wayward children as the latter spun a counterculture that attacked many of the World War II generation’s dearest assumptions, most of all its respect for conformity.

It was not a surprising optimism, really. The children of these conformist parents were acting on lessons learned inside cozy suburban houses. They truly believed that America could be anything it wanted through its wealth and power.

That utopia collapsed onto a hillside at Kent State. There, the children of the Greatest Generation wailed over friends’ bodies killed by friendly bullets from guns held by still other children of that same generation.

And the dominoes kept falling, affecting even the stars of Woodstock. In September 1970, Jimi Hendrix died in London of barbiturate-related asphyxia. By October, Janis Joplin was dead of a heroin overdose after failing to show for a recording session.

Utopias can become brutish. The French Revolution succumbed to the guillotine. The Bolshevik paradise festered in gulags. The 1960s were not so bad as that, of course. If anything brought them down, it was the belief that optimism alone was enough, that simply believing in a better world could conjure it into existence.

The journalist Hunter Thompson later would write the obituary for this movement and its quest for “the inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil.”

In Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, Thompson remembered this of his fellow counterculturalists and their beliefs: “Our energy would simply prevail.There was no point fighting; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.”

Looking back on that lost dream, Thompson’s observant eyes aimed west and traced a line he saw closer to San Francisco. There, he saw the high water mark where the idealistic wave finally broke and rolled back to the sea.

© Robert Craig Waters 2020. For this and other writings: http://www.robertcraigwaters.com

And here’s hoping the current wave has reached its watermark and will roll back into the gutters where it came from. Good article Craig.

LikeLike