When is it safe to end social distancing? Does history tell us anything? Perhaps it does.

Just over a century ago, there were events similar to what is happening today. Pandemic influenza swept the globe in 1918 at the end of World War I, much like coronavirus has done today. The so-called Spanish flu spread from city to city in the United States, eventually killing about 675,000 Americans by the time numbers began to decline in 1919.

America’s large cities each confronted the 1918 pandemic with different approaches under the municipal public health system that existed at that time, which was different from today’s system giving states and the federal government much larger roles. Some strategies in 1918 were successful, some only seemed successful until numbers were tallied, and some were deadly failures. Cities falling into these categories include St. Louis, San Francisco, and Philadelphia

Today, many historians agree that one of the most successful strategies was used in St. Louis, Missouri, through the leadership of a politically astute health officer. Under Dr. Max C. Starkloff, St. Louis began preparing early when news first arrived of a contagion sweeping Boston.

Dr. Starkloff used his political connections with the city’s Republican mayor and other city leaders to put surveillance systems in place among a network of local doctors before the flu even arrived. Once these doctors began reporting infections, Dr. Starkloff persuaded the city to cancel parades and other public events, order increasing restrictions on businesses and churches, and shut down schools.

Always facing strong criticism, Dr. Starkloff worked constantly to build consensus through his political network. He met with retailers and convinced them to stop advertisements that brought too many people into stores on weekends. He held reluctant church leaders at bay with help from the mayor. When teachers were sent home by school closures, he persuaded many of them to help out in public health programs.

After misinformation became a problem, Starkloff assigned a staff physician to monitor and supervise communications with the public and the press – a position that today would be called a public information officer. Unlike other city health officers in the nation, Dr. Starkloff refused to back off of social distancing even when people grew weary or angry.

When pandemic conditions finally became milder, Dr. Starkloff gradually eased back on St. Louis’ social distancing. But he also monitored conditions closely. The 1918 flu was prone to wane and then surge again. So, when cases began to rise again, Starkloff reimposed social distancing measures. This included shutting the schools a second time after a sudden spike in the numbers of infected children. The 1918 flu seemed especially prone to kill the young.

Compared to other cities, St. Louis kept its social distancing measures in effect for a longer time, until the number of infections dropped below a benchmark set by the consensus of local doctors. Starkloff’s work dampened public pressure to reopen the city too soon and helped keep St. Louis’ pandemic death toll at 358 per 100,000 of population, a low number compared to other cities.

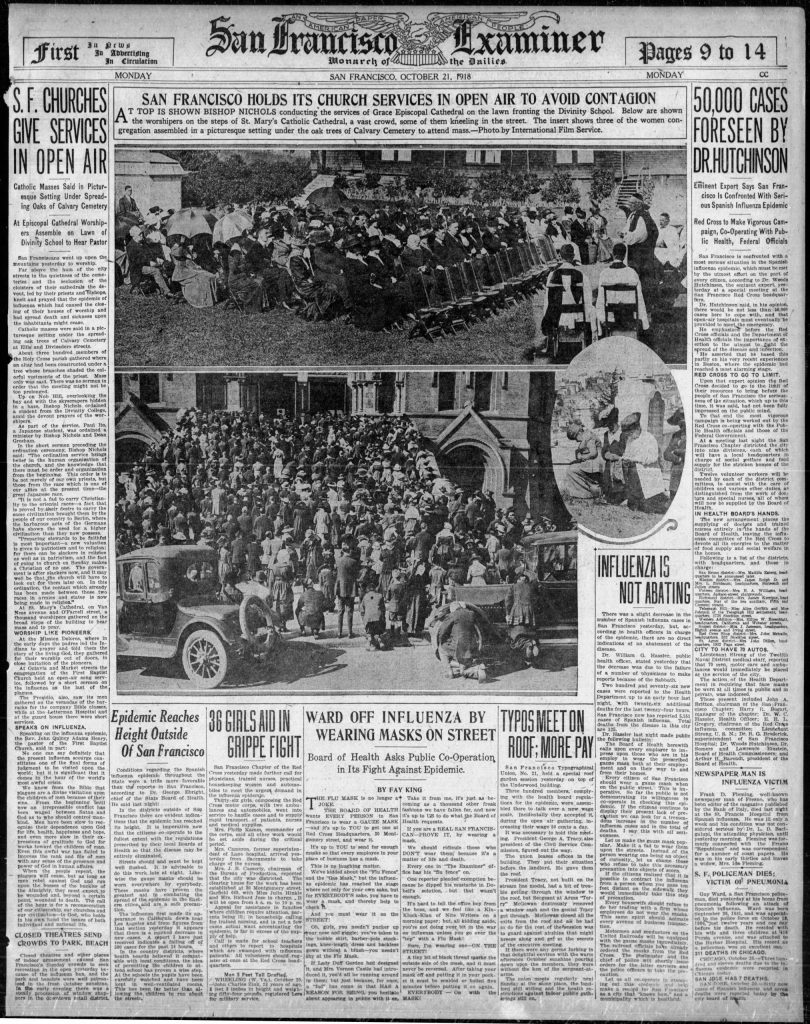

In contrast to St. Louis was the approach followed in San Francisco. The city by the bay had its own health officer, Dr. William C. Hassler. From the start, Dr. Hassler was hesitant to order closures. When infections surged, he and city leaders partly relented and ordered limited closures. But they exempted a number of large gatherings including church services and some public events. Instead, San Francisco leaders seemed persuaded that people still could gather at some events if they did so outdoors or used face masks, as shown in photos from the time.

Using face masks, in fact, became the signature element of the San Francisco approach, especially at indoor events. Businesses like barber shops, for example, were allowed to remain open if barbers wore masks. So were hotels, banks, and some other kinds of stores so long as their staffs were masked. San Francisco nurtured a belief that holding meetings outdoors afforded safety from infection. Photos from the period show court sessions being held in parks, outdoor church services with people packed together in chairs, and large military parades associated with the World War. But even the use of face masks proved controversial, eventually giving rise to an outspoken group of dissenters called the Anti-Mask League.

When the first significant dip in infections came, Dr. Hassler and city officials decided to lift most restrictions. An official ceremony for removal of face masks turned into a city-wide celebration in which San Franciscans gathered in the streets, waited for the blow of a whistle, and pulled off their masks and threw them into gutters. Local newspaper headlines touted the event as the “disappearance” of influenza. It was anything but that.

Within a few days, the number of infections rose again. At first, Dr. Hassler argued that the increase came only from outsiders who had ventured into San Francisco from elsewhere. Rather than restrict businesses again, the city recommended a voluntary return to the use of face masks. Another dip in cases followed, convincing everyone that further measures were not needed.

Then came a single day when more than 600 new cases of disease were reported. Once again, the city ordered mandatory use of face masks. A backlash at these on-again, off-again orders was almost immediate. People argued that the masks had proven ineffective, which probably was true because other forms of physical distancing had not been used consistently. Angry at city officials, the Anti-Mask League held a public rally of some 2,000 unmasked demonstrators.

By this point, the epidemic already was declining nationwide. It also began to fade in California. Throughout the ordeal, Dr. Hassler proclaimed that San Francisco was the only large city to contain its epidemic so quickly. On the whole, the city seemed pleased with its effort and lauded Dr. Hassler. It was only later, when final numbers were compiled and compared, that people realized San Francisco had endured one of the worst losses of any major city in the United States. Its pandemic death toll was 673 deaths for every 100,000 of population.

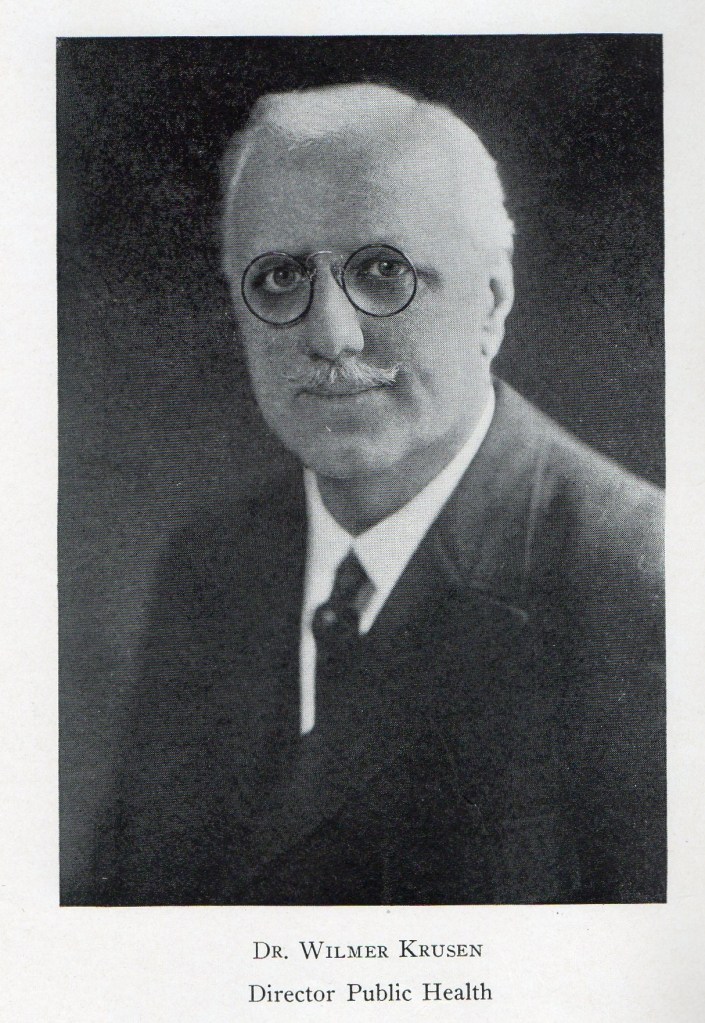

If San Francisco deluded itself into a phantom success, other American cities were under no such illusion about their failings. Philadelphia was one of the most obvious. From the start, its health officer Dr. Wilmer Krusen labored under false assumptions about how the disease spread. He assured the public that everyone was safe so long as anyone with influenza was isolated, not realizing that the virus could be spread by infected people before any symptoms appeared.

At first, his false assumptions appeared to hold true. The number of cases seemed to drop. Based on this evidence, Dr. Krusen told the public that there would be few deaths and that isolation of the sick soon would stop the outbreak. He took the additional step of requiring local doctors to report all influenza cases so they could be tracked. But beyond these measures, he saw little need to halt normal city life, especially activities associated with World War I.

Philadelphia like many American cities took great pride in patriotic events meant to raise money for the war through bonds. Bond rallies and parades were common at the time, and cities competed with each other to see which one could raise more money. So, despite the pandemic, Philadelphia proceeded with its fourth large Liberty Loan parade downtown, drawing about 200,000 people to watch military men in formation, a rolling display of weapons of war, and the marching band led by John Philip Sousa.

Only days after the parade, Philadelphia’s epidemic exploded. The city hospital system was soon overwhelmed. Funeral homes and morgues filled beyond capacity, and reports said some families were forced to bury their own dead. An estimated 50,000 Pennsylvania children were orphaned. Shocked at the sudden surge in deaths, Pennsylvania’s governor ordered statewide closure of places of amusement and many other businesses. The state’s economy plummeted. Many companies later estimated huge economic losses caused by the shutdown.

Throughout the surge in cases, Dr. Krusen and other authorities continued to assure the public that things were not as bad as some said. They argued that the real enemy was panic. Against the evidence, leaders assured the public that the virus could be defeated by positive attitudes and a clean lifestyle. Complaints against the state government’s closure orders were rampant and divisive. In the end, Philadelphia’s pandemic death toll was one of the highest of any large city in the nation – 748 fatalities for every 100,000 in population.

Are there any lessons to be learned here? In retrospect, the St. Louis approach was more successful in reducing deaths because it started early, built widespread consensus among stakeholders, used a variety of programs to reduce infections rather than relying on any single one, and was flexible in adjusting social distancing as the pandemic repeatedly surged and waned. San Francisco was less successful because it placed too much emphasis on face masks and lifted this and other safety measures too soon while letting large crowds gather for certain kinds of events. Philadelphia meanwhile suffered a high death rate because of an inability to understand how the disease spread and a failure to cancel a socially popular parade at the most crucial time.

For source material and more information on how the United States’ major cities were affected by the 1918 pandemic, see this historical website: https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/

I wonder what will be said about various cities handling of this current virus 100 years from now. Will we have learned anything?

LikeLike

The coronavirus pandemic will be studied for centuries for the lessons it holds.

LikeLike