Going back to beginnings later in life is never easy. But at some point in every life it is necessary. — To see the place of origin. The place where the ripples in time began, where the stone fell into the millpond, spawning circles that grow and grow. Echoes that continue even to this day.

I undertook that journey on July 18 this year after a family funeral in rural Alabama.It was the funeral for my Uncle Joe Weaver.

I am descended, as was Joe, from the Bookers of Conecuh County, Alabama. My grandmother Viola was a Booker before she married a North Carolina man named Joseph Barnett Weaver whom she met in Ohio while looking for work. They came back to Conecuh when my grandfather’s asthma made snowy Akron too fraught a place for him to live.

The Bookers have been in Conecuh since settlers first came here after a young United States seized the land from those who held it before.

Many curses rose up as blood seeped into red soil. They still are reflected in names you find everywhere. — Names like the Village of Burnt Corn, where my father was born. Cornfields were burned, my grandfather told me as a boy, when natives fought settlers brought to the red clay hills by Andrew Jackson’s invading army.

Plunder breeds ghosts that haunt conquerors and their heirs. And so, to this day, ghosts linger on this land in the place names of Conecuh, and in more besides. Names are just another kind of ghost.

I felt the ghosts again on July 18 as I journeyed over red clay roads to travel back to my family’s beginnings. Driving my little beige Honda Accord, I crossed a stream called Murder Creek. — So named, I was told as a child, because dead troops and warriors were heaped into its water in the Creek War of 1813 and 1814.

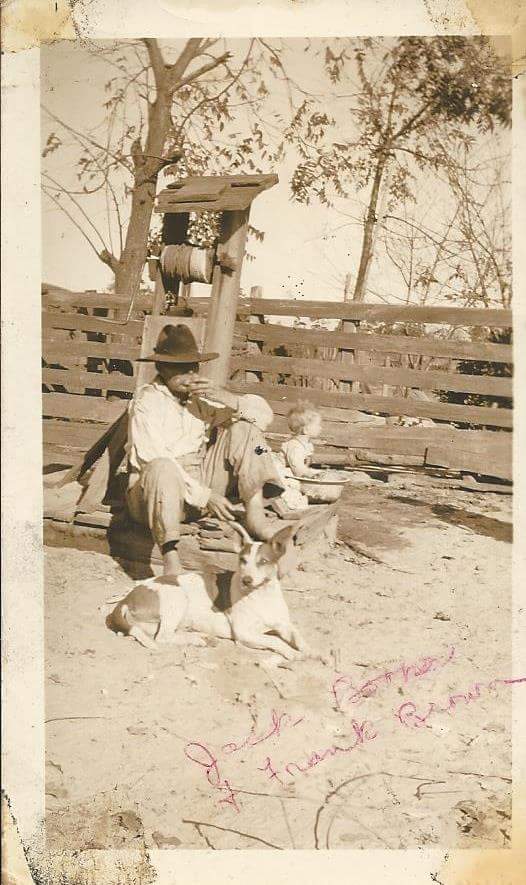

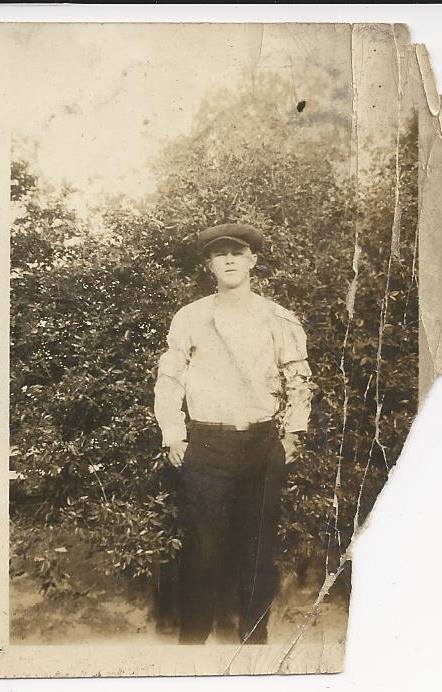

And there are still other names. Family names. My great-grandfather and his youngest son both bore the name Andrew Jackson Booker — shortened to Jack. In honor of its ghosts, the family continued to name its sons after the populist general who gave them homesteads he had taken from others.

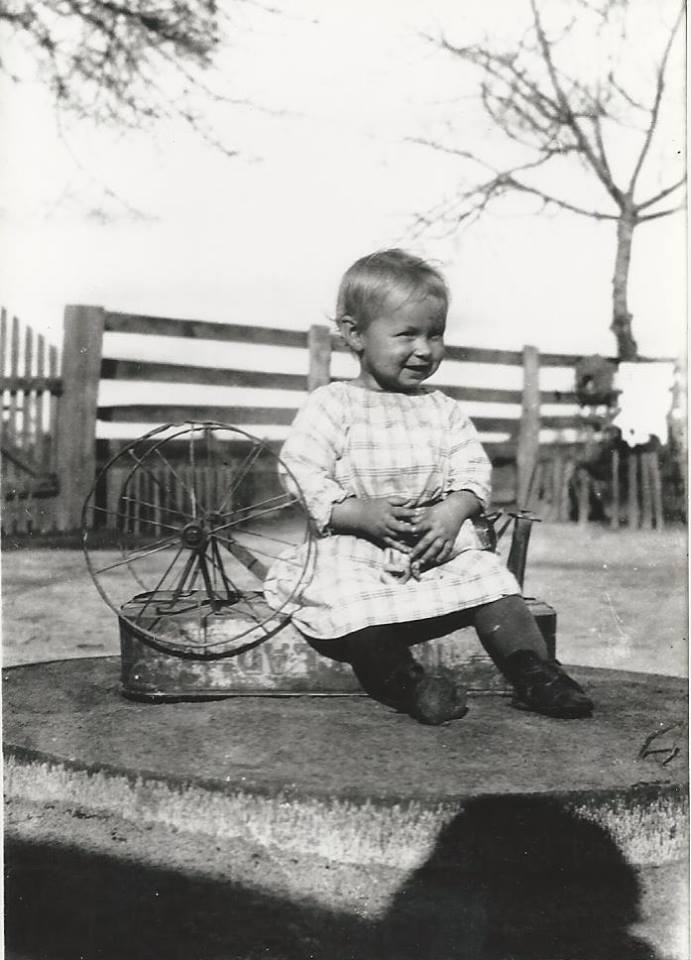

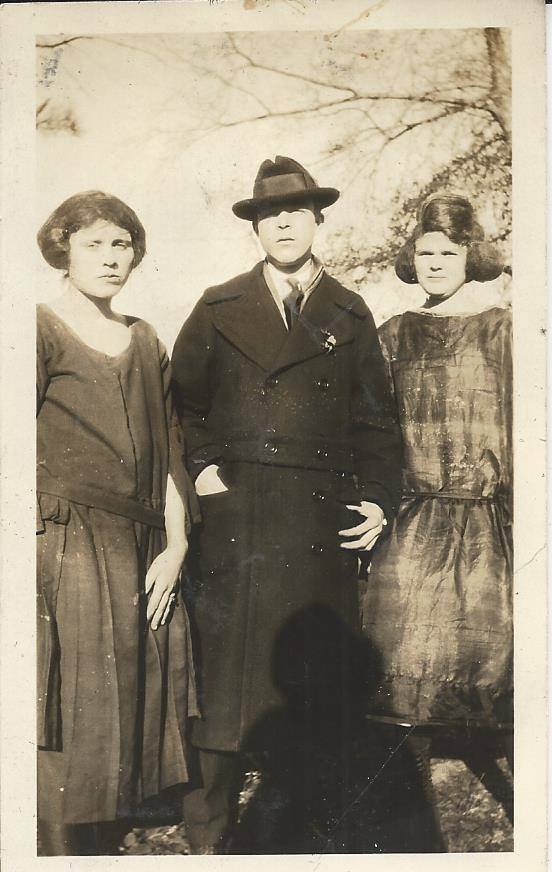

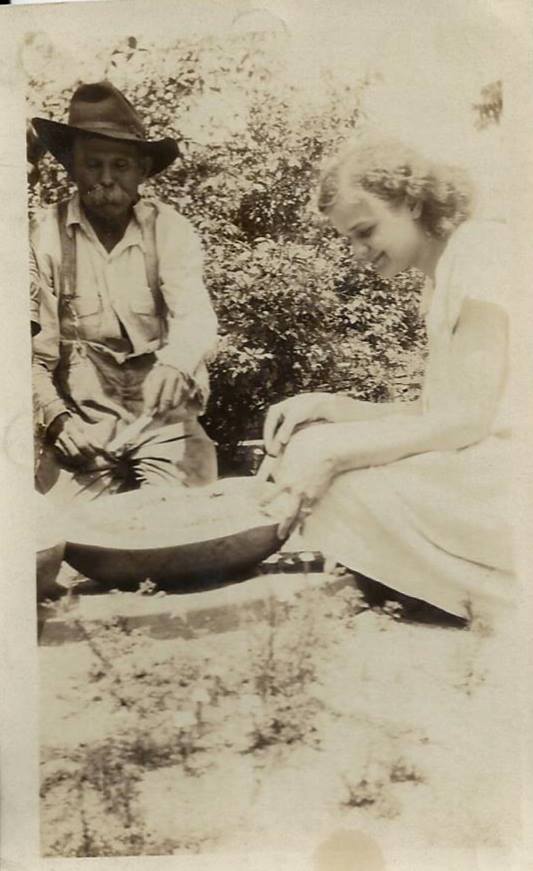

I have many photos of my great-grandfather, who was a fire-eyed country man with a cascading mustache. He and his wife Minnie Evelyn Mooney Booker bore six children that lived to become adults. They and my grandmother entered my life as family who seemed a fixed constellation at the moments my first memories formed.

I knew them by the names my mother used. First, there was my Uncle Frank who taught me to collect coins and gave me handfuls of mercury dimes and a Civil War commemorative plate I still own. Frank always drove a Cadillac with a well tended clutch of bottles in its trunk.

Then there was eagle-eyed tee-totaling Uncle Jack who never talked about his battles in World War II, though I always knew they had happened and could not be discussed. After retirement, this younger Jack bought and moved back into the little cabin where he had been born in Conecuh’s hinterlands.

There was our rag-lady Aunt Anner — her name, a backwoods contraction of Texanna — who was rich from rental property she owned in Akron. Yet she lived like a pauper and would not show anyone her remarkable skill at cooking unless they bought the groceries and brought them to her house.

And there also was Aunt Mothy — a variation of Martha — who was distant from the rest of the family and never seen at family events. Her absence was always present. The rift had happened because of hazy resentments created long before I was born when her father, Andrew Jackson Booker, favored her above his other children.

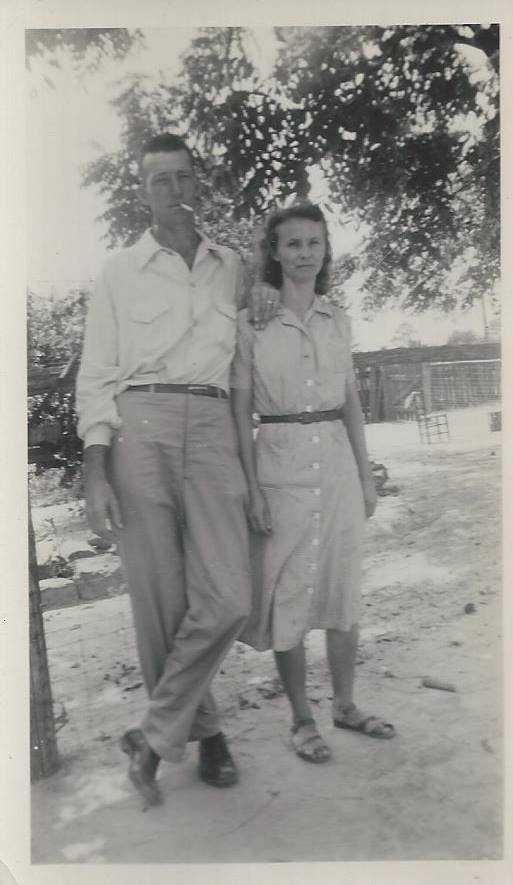

There also was lovely Aunt Mae, the beauty of the family. She became a vivacious flapper in the 1920s who loved fine clothes and roses, relished manipulating her menfolk, and through the years discarded husbands who routinely failed to meet her expectations.

My grandmother Viola Booker Weaver rounded out the six, with her name fixed as WeeWee because my sister as a tot found “Grandma Weaver” hard to say. WeeWee was beloved by all her grandchildren, though all of us knew that her life was tragic in a way that hid behind smiles and laughter.

And there was a seventh, Aunt Jess. She was my grandmother Viola’s firstborn and my mother’s half sister. Jess had been born before my grandmother married, something never talked about and never forgotten. Jess had been taken and raised by my great-grandparents, Jack and Minnie Evelyn Booker, in their little house near Spring Creek in Conecuh County.

The house is still there. I saw it in July. This old house that my great-grandfather Andrew Jackson Booker built. It is still standing there in the woods. I found it again on July 18 as I traveled backroads after the funeral.

It was a log cabin in my childhood, but clad in 1970s siding today. In my memories, it first came into my life when my mother took me to visit her half sister when I was just a preschool boy. Aunt Jess had received the homestead after my great-grandparents died and left the land to the child they sometimes said was their youngest daughter. And Jess, in turn, later sold the land to Uncle Jack.

In July this year, I might have missed the old house as I drove past it if I had not seen its chimney made of field stones. As a little child the stone fireplace fascinated me with its cavernous ancient look.

It all was so long ago now. Scores of year in the past. There was a day in one of those years when I sat at that field-stone fireplace and listened to my mother and Aunt Jess talk. And I entertained myself by throwing little fat lighter pine stump splinters into the fire to watch them flare and vanish.

Wary of my boyish fascination with fire, my mother had shooed me into the yard to play alone. And there, I encountered my first flock of gray and white farm geese. Birds as tall as I was, with chicks I longed to pet.

I reach toward one. But the gander was quick. He screeched and screamed and ran toward me, chasing me behind my mother’s big black Oldsmobile near the field stone chimney. I stood there shivering in a yard covered in white sand meant to make rattlesnakes easier to spot, lest someone get snakebit.

On July 18, 2019, I stood shivering behind my own little beige Honda in the same yard near the same chimney in a yard now devoid of white sand, full of weeds where serpents might lurk. I gazed toward the place where the gander had charged me nearly 60 years ago.

My pulse raced. I felt a sweat. And I shivered again as I absorbed more ripples in time.

© Robert Craig Waters 2019