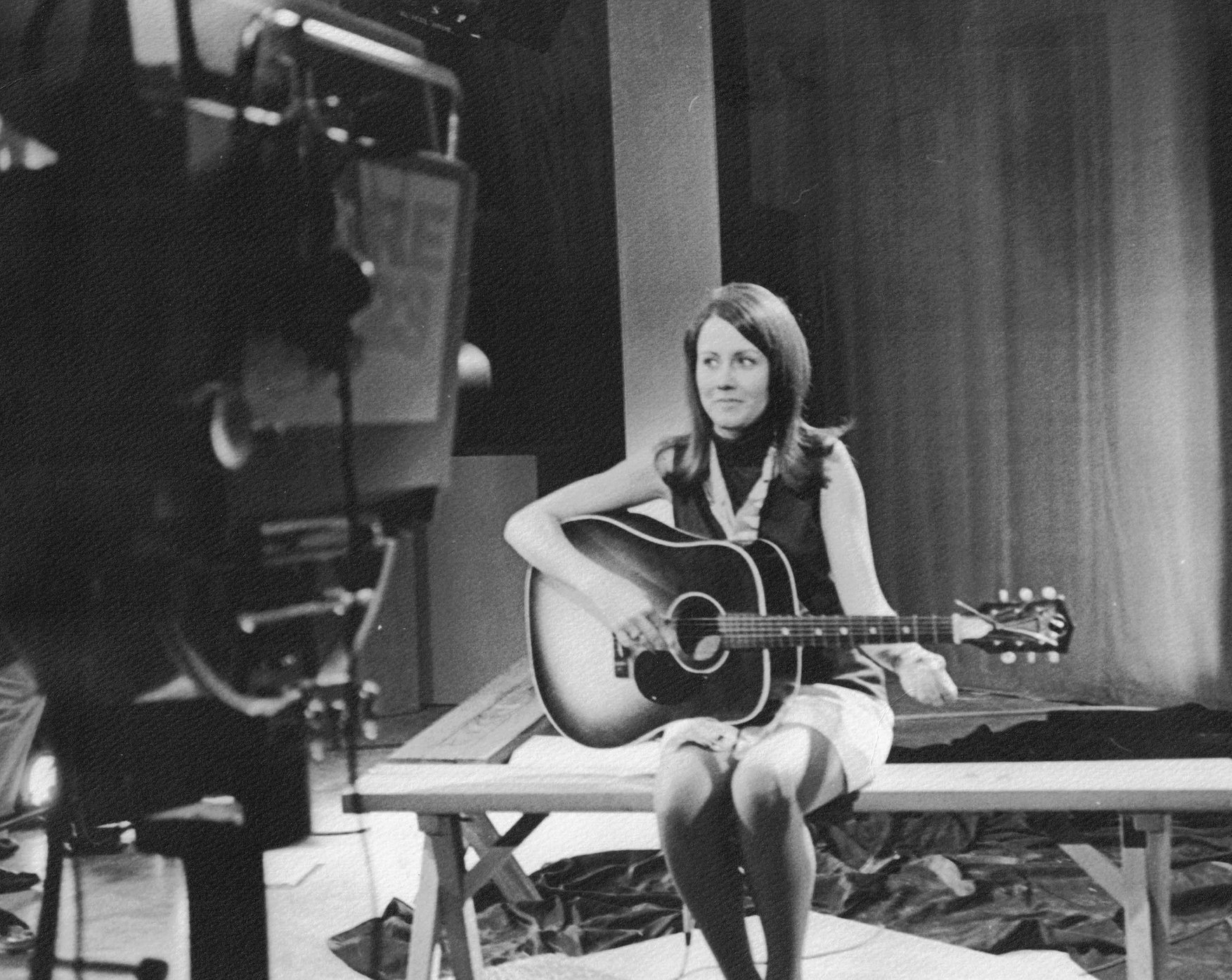

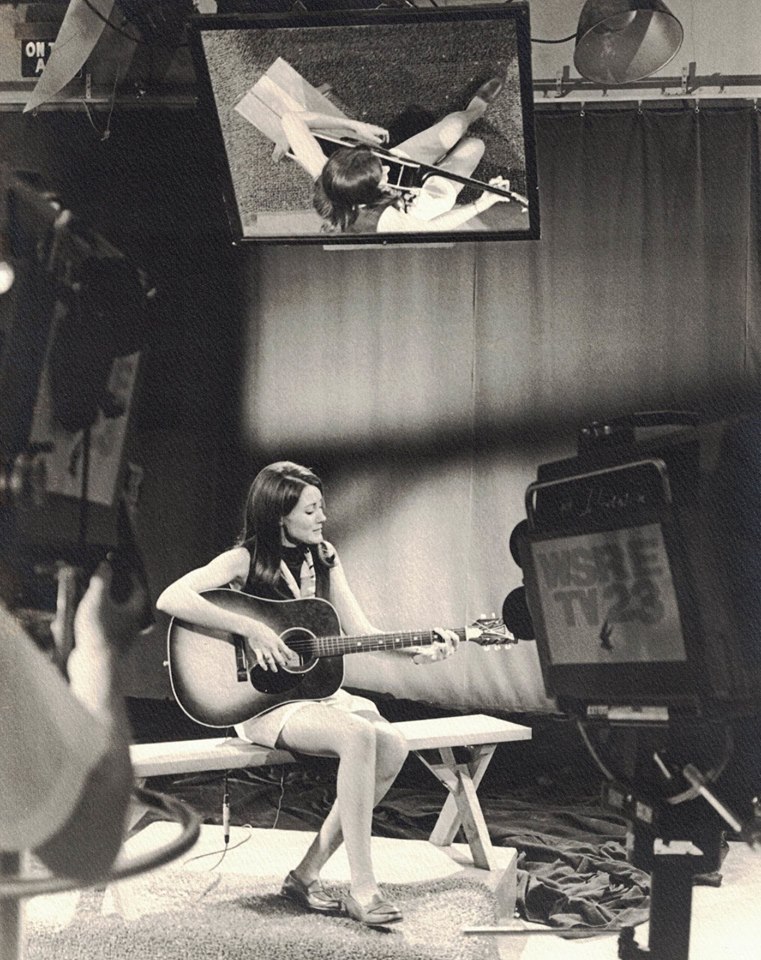

Around 1970, my sister Debbie Waters Box was a young singer just starting a career as a music teacher when the local PBS station in Pensacola asked her to make some recordings for use in folk music studies. She took me along to watch.

I was only 14 and had never been inside a TV studio. It was a place of marvels to young eyes. — Large studio cameras. Lights dangling from a dark ceiling. Background props that looked so fake in person but so real in the final broadcast.

WSRE Television was located on what then was the campus of Pensacola Junior College near the airport. And the station already was making a name for itself as a progressive voice in a conservative Deep South town.

Someone — an old friend of my sister’s — took pictures of the recording.

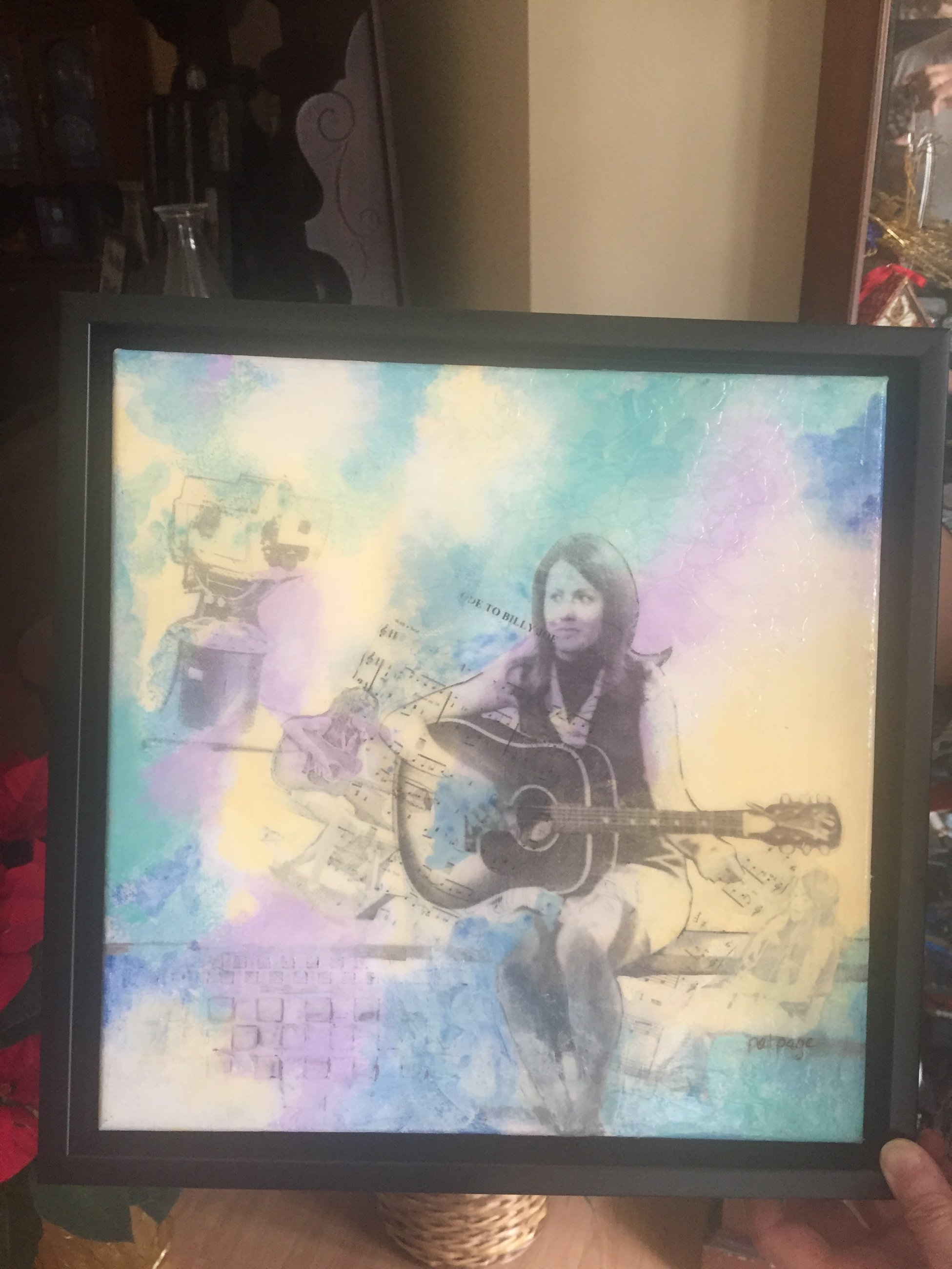

When my mother died in 2006, I found three of the printed black-and-white photos stored away in a box of mementos in the back of a closet. They instantly brought back a rush of memories.

Debbie recorded a number of songs that day at WSRE as I sat in the dark part of the studio and watched. But one song stood out in particular. It was Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billy Joe.”

As a child, I always was captured by the words of my sister’s songs, which I parsed carefully for meaning. Once when my sister sang “Puff the Magic Dragon” to me for the first time, I burst into tears when she got to the verse that said, “A dragon lives forever but not so little boys.”

And then there was this: “Today, Billy Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge.” The words of the song mesmerized me.

A Southern family very much like my own was sitting at the dinner table casually wondering why a young neighbor boy had killed himself. There were hints that the young lady singing the song had been seen earlier with the boy Billy Joe throwing something off the bridge where the suicide later occurred.

Why? As a child, I always wanted answers.

But the song provided none. Its lyrics ended with a cryptic message: The singer herself later returned to the bridge to throw flowers into the muddy waters of the river below.

This is one of my first memories of a concept that was still new to me in 1970. — Some questions don’t have answers.

Only a few months later in early 1971, my ninth-grade English teacher at school started a lesson plan on folk music. Our first assignment in class was to watch my sister sing “Ode to Billy Joe” in a recording and then discuss with each other what we thought the song meant.

My classmates raised many possibilities. Perhaps Billy Joe was unhappy living in the rural town of Choctaw Ridge. Had a doctor just told him he had cancer? Maybe the young lady singing the song had undergone an abortion and the child was Billy Joe’s.

But then one classmate raised a question that made the entire classroom go silent. Even the teacher herself was speechless. — Had Billy Joe committed suicide because he was gay?

In that single moment, the words of the song sung by my sister took the shape of something symbolic. And the symbol loomed large in my life for the remainder of my teen years and well into my twenties.

Because in 1971 I was just beginning to have questions about my own sexuality while living in a sleepy, dusty Southern town very much like Choctaw Ridge. And I was just starting to see that the answers would not be easy, if they existed at all.