My Great Aunt Mae was a mild-mannered firebrand, a woman who kowtowed to men while also dominating them, a self-made woman in sole charge of her own life at a time when doing so was viewed with deep suspicion.

And she was one of my heroes. — One of the people who forged my own abiding sense of independence.

Early in my life, I learned that this woman — born Minnie Mae Booker — was the exception to every rule applied to the women in my family. And from what I saw, she was happier than any of them.

I spent countless summers and Christmases with her until she died in 1977 when I was still a student at Brown University. She always left me in awe of what she had done.

Born in extreme rural poverty in Conecuh County, Alabama, Aunt Mae had followed her brother north toward the promise of jobs in Akron, Ohio.

It was a time in the early Twentieth Century when the burgeoning auto industry created huge demand for rubber tires. And Ohio at the time was the center for tire manufacture.

Mae found work in the tire factories — and a fully independent life even before the Great Depression began. It was a solid middle-class life, though in my childhood I thought she was as rich as a Rockefeller.

My earliest memories reflect the division of my Deep-South family between its Alabama roots and its Ohio cousins. For the longest time the family’s assumption was that our relatives in Akron were Southerners who had agreed to become — Heaven help us — Yankees in exchange for vast amounts of money.

And by the standards of my childhood, they were fabulously rich. Aunt Mae bought whatever she wanted, always wore the best clothes, showered my sister and me with undreamed-of gifts, and lived in a house she owned in her own right.

No man was involved in her money. None at all. That was shown without any doubt when she divorced husbands as freely as she wanted. — And they were the ones who had to leave the house, not her.

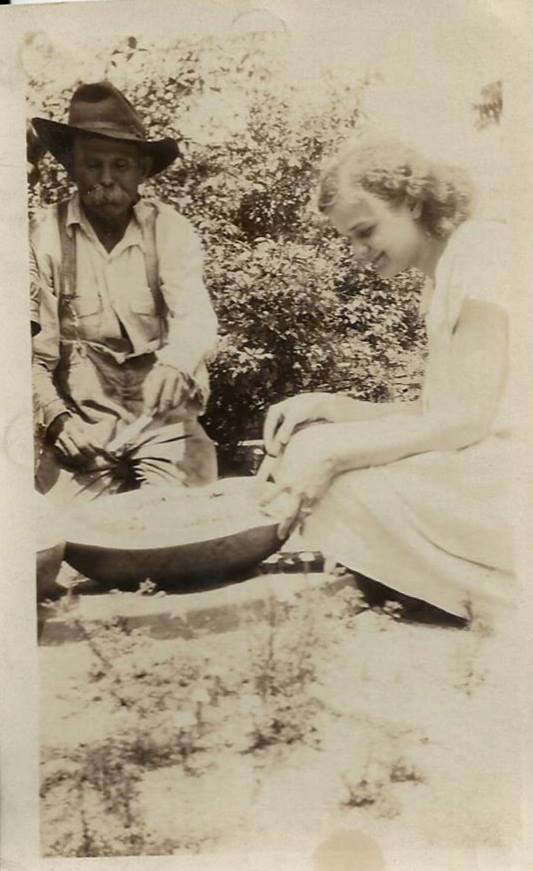

Mae was a flapper in the 1920s. She wore pants suits when doing so was viewed as an affront to established morality. She often complained about her husbands and their fickle ways. Once she said, “Honey, I never was any good at picking my menfolk.”

Actually, her husbands as a rule were not worthy of her. They wanted to subjugate her. — And that was something she never allowed, no matter how much she wished the marriages would continue. Aunt Mae was far too smart for that.

She is with me even now, here today, here with me as I write this down.

I think of her every day, more than 40 years after she left the world.

I remember her house on Herberich Avenue in Akron. It was her own piece of property — land that no one could take away from her, not even the men who wooed their way into her life with promises they did not keep.

Most of all I remember her independence. — And I still admire her for it.