No historic place in the Big Bend and Tallahassee area has been more overlooked than this one. — Prospect Bluff on the Apalachicola River was the site of one of the largest massacres of runaway slaves ever officially ordered by the government of the United States.

It happened on July 27, 1816, at a strategic rise of land on the riverbank known as Prospect Bluff. Jim and I visited the site this past weekend.

In 1816, Florida was still a Spanish province. But the northern part of Florida was under the effective control of American military forces commanded by General and future-President Andrew Jackson.

What caught Jackson’s eye at this place was an old British fort that controlled a critical bend in the river just south of today’s town of Sumatra, Florida. The Apalachicola was then a crucial link for exporting cotton from plantations in Georgia and present-day Alabama.

The people who owned those plantations already were complaining loudly that their slaves were escaping to freedom in Florida. It was the nation’s first Underground Railroad — a precursor to the abolitionist movement of later decades.

After losing the War of 1812, the British military had turned the fort over to escaped slaves and their Seminole allies. This “Negro Fort,” as Jackson called it, had become a beacon of hope to American slaves yearning to escape bondage.

Runaway slaves were streaming into the area and establishing their own farms and a kind of government along the banks of the river.

Spain had long had minimal interest in its Florida territory, which was far less economically important than its provinces in Latin America. It spent little effort trying to police Florida’s residents and sent no military force to back up its complaints about American incursions.

The United States, on the other hand, had developed a keen interest in Florida after the British seized parts of it in the War of 1812 and used its strongholds there to harass American military efforts.

American leaders of the day also had come to view the thought of an independent Florida with rising terror because of its proximity to the slave states of the South. Florida easily could become a place like Haiti, they feared, where the enslaved people already had revolted against white overlords and established their own independent government.

Andrew Jackson did not conceal his intentions about the “Negro Fort” along the Apalachicola. He wrote out an ominous order to his officers in April 1816.

“I have little doubt of the fact,” Jackson said, “that this fort has been established by some villains for rapine and plunder, and that it ought to be blown up, regardless of the land on which it stands; and if your mind shall have formed the same conclusion, destroy it and return the stolen Negroes and property to their rightful owners.”

On July 27, 1816, his officers did exactly that. From a gunboat in the river, they heated cannon shot in the galley kitchen until they were red hot.

One of those cannon balls screamed into the fort’s magazine full of gunpowder. It exploded with the results Jackson intended. — About 300 escaped slaves and their wives and children died in the blast or were killed by American troops as they lay stunned on the ground when Jackson’s forces came ashore.

One eyewitness Lt. Col. Duncan Clinch described the scene. “The explosion was awful,” he said, “and the scene horrible beyond description. Our first care, on arriving at the scene of the destruction, was to rescue and relieve [kill] the unfortunate beings who survived the explosion.”

African Americans who survived were taken north and “returned” to the possession of white plantation owners who claimed to own the ancestors of the runaways.

The utter destruction of the “Negro Fort” was the opening volley of the First Seminole War that wracked Florida for the next three years. It ultimately led to Spain finally bowing to the growing American power when it ceded troubled Florida to the United States in 1819.

But Florida remained a quarrelsome place for decades. Many escaped slaves melted into Seminole culture and continued to fight American forces in the three different “Seminole Wars” that lasted until 1858, just before the Civil War started.

Some of the descendants of the these former slaves today are recognized as “Black Seminoles” after they became a part of the tribe.

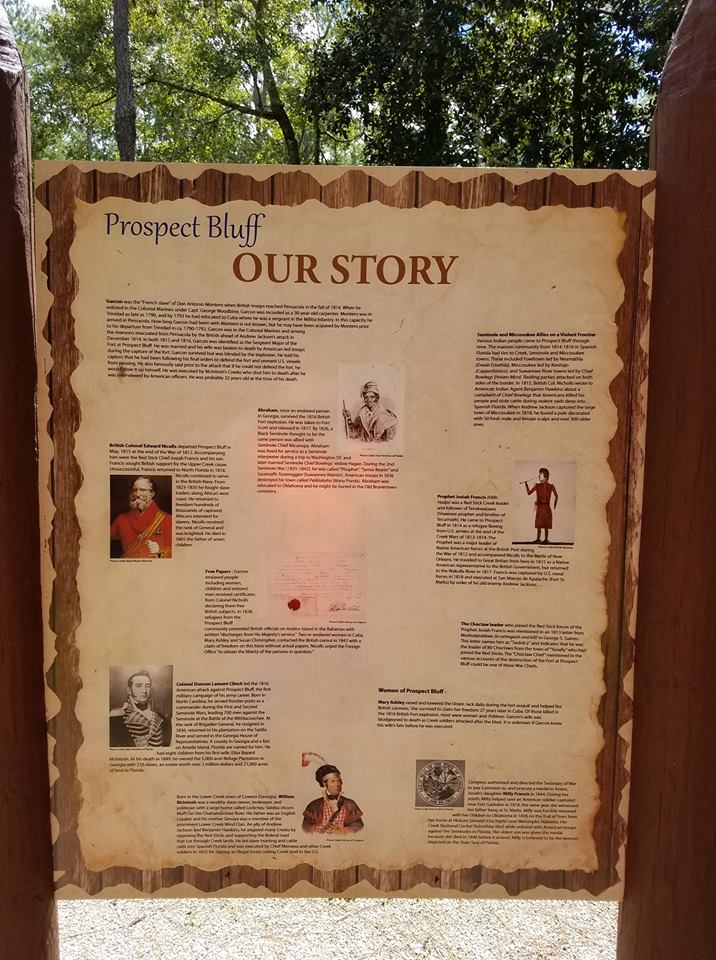

The site of the massacre at the Negro Fort is maintained by the U.S. Forest Service today and has a few displays and a picnic area. In 2016, a gathering was held at the site commemorating the 200th anniversary of the fort’s destruction.

Earthworks from 1816 and later fortifications still are visible. But the site itself is largely undeveloped and little recognized, sitting at the end of a long and often muddy dirt road.

Yet it marks a critical point in American history that deserves far greater recognition than it has received to date.