In the law, ripples from the past moving forward in time are called precedents. Earlier events set models for handling future events. History influences the present. What’s past is prologue.

So it would be in 1857 when the Florida Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in a quarrelsome case involving one of early Tallahassee’s wealthiest families. — The Crooms, owners of Goodwood Plantation.

The facts of the legal case were classic law-school material that would become a puzzle for student lawyers on countless final exams. Just before moving to Tallahassee to make a new home there, the entire Croom family perished at sea aboard the steamship SS Home off the coast of North Carolina in an 1837 hurricane.

The father, Hardy Croom, already had sold much of his property near New Bern, North Carolina, and had moved his slaves to Goodwood Plantation at Tallahassee. His new house was being built there. But his wife and children had not yet set foot in Florida.

Worst of all, Hardy Croom, only 40 years old, died without a will. He had told his brother that he had written his Last Will & Testament before setting sail, but it was never found.

On October 9, 1837, the “Racer’s Storm” ripped the SS Home to pieces on the Outer Banks, drowning most of its passengers. Dead were Hardy Croom, his wife Frances, his daughters Henrietta and Justina, and his son William. There were no other children.

In legal terms, the family all died in a “common calamity.” The lawyerly issue was this: When parents and all their children die together in a common calamity, who inherits the family fortune?

In this case it was a considerable fortune indeed, consisting of more than a thousand acres of prime plantation land only a few miles from the Florida capitol.

But the most valuable asset was something less familiar in today’s world — the slaves of Goodwood Plantation. They numbered as many as 200. Just before the start of the Civil War, the average price of slaves was more than $20,000 each in modern dollars, by some estimates.

The legal arguments hinged on two issues. First, what was Hardy Croom’s legal residence at the time of his death? And second, which one of the Croom family members died last in the shipwreck?

Legal residency determined which state’s law governed the case. Florida law at the time favored giving the plantation to Hardy Croom’s brother Bryan. Bryan Croom already had taken control of Goodwood after his brother’s death — managing the plantation and finishing its mansion house over the next 20 years before the lawsuit and appeals ended.

But North Carolina law favored someone else — Hardy Croom’s mother-in-law Henrietta Smith. She already had been named the executor of the Croom’s separate estate in North Carolina. Unhappy with what was happening in Florida, she later challenged ownership of Goodwood after Bryan Croom refused to give her a settlement of half of the Tallahassee property.

The most troublesome issue was the grim question of who died last aboard the disintegrating steamship. Without a legal will, the law mandated that Hardy Croom’s property must pass automatically to his children if they outlived him by even a few minutes.

And if they did, their closest living legal relative was their grandmother Henrietta Smith. On the other hand, if Hardy Croom himself died last, his closest living legal relative was his brother Bryan Croom.

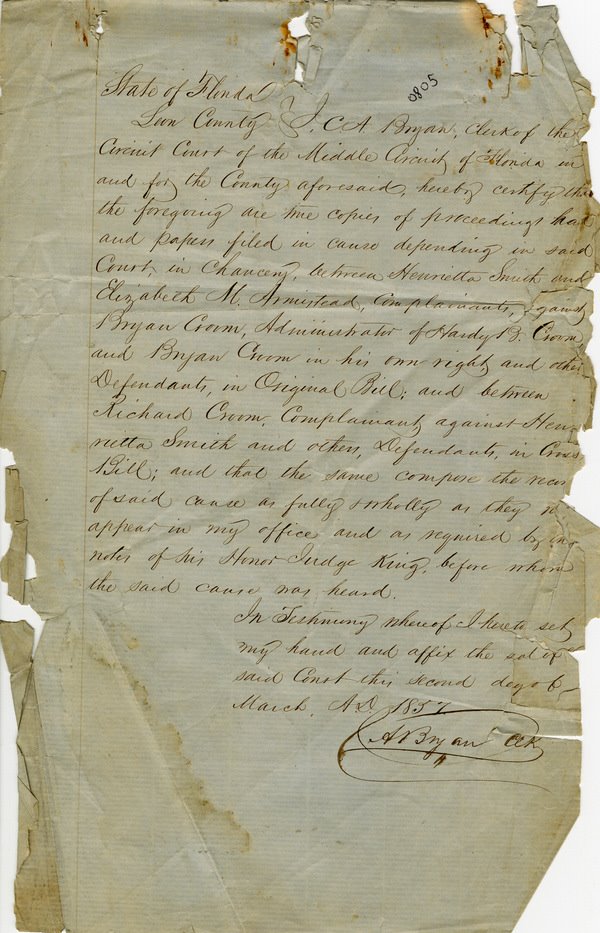

That is how the case itself became known to history as Smith v. Croom.

Testimony in the Leon County court case focused on the ill health Hardy Croom had suffered much of his life. He had a “feeble” constitution that left him “incapable of much physical exertion beyond a short walk,” court documents said.

Based on that evidence, the Florida Supreme Court in 1857 agreed that Hardy Croom would not have lasted long struggling against an Atlantic storm as the SS Home fell apart around him.

So, the Court concluded that his son William was the last survivor. And that meant inheritance rights flowed through William to his grandmother Henrietta Smith. She would become the new owner of Goodwood Plantation and the enslaved people who tended it.

Smith v. Croom stands as Florida legal precedent today on a number of points. Its rules about simultaneously death in a common calamity are still studied in law school, though they have been modified over the years.

What happened to Goodwood? The legal fight over its land and slaves had lasted 20 years before it was resolved by the state’s highest court. Losing his case in the end, Bryan Croom was forced to pack up his belongings and hand the plantation over to Henrietta Smith.

She, in turn, sold it to someone else in 1858.

The new owner’s name was Arvah Hopkins, a wealthy New Yorker who would dazzle Tallahassee before he lost everything in the Civil War. Though born a Yankee, Arvah Hopkins soon became more Southern than a Rebel Yell. But that is another story.