It was Tallahassee’s own Trail of Tears. But in its day it would have been called simply a “coffle.”

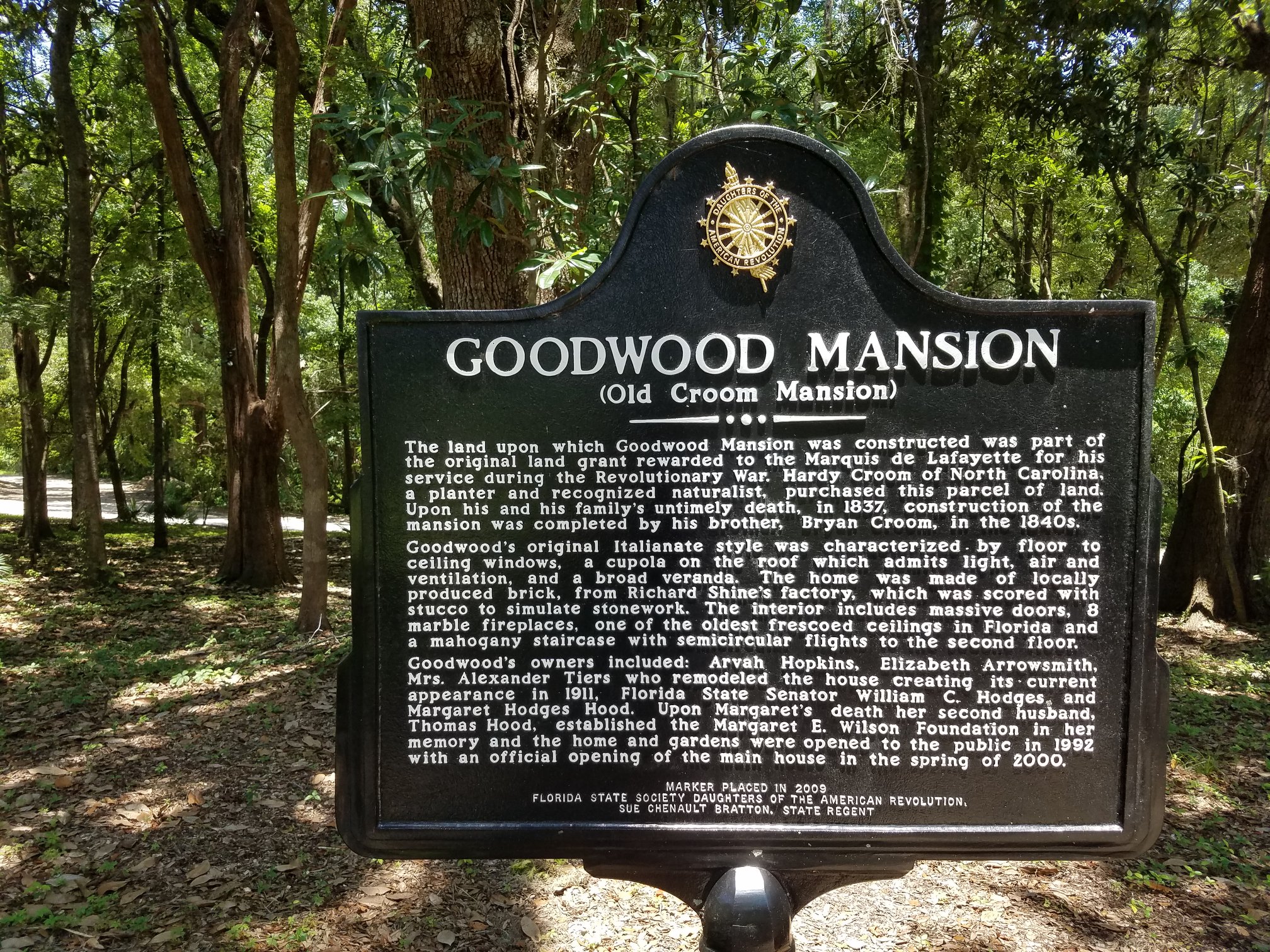

And it ended here at the lawn of Goodwood Plantation in Tallahassee.

Yesterday, I looked out over that same lawn just steps away from the capital city’s largest hospital and imagined the scene that happened in the early 1830s.

Some 200 enslaved people — the exact number is not known with certainty, according to our tour guide — were marched here in a three-month trek from the only home they had known in North Carolina.

They marched down the trail that would become today’s Miccosukee Road and onto land where they would be forced to work until they died, and their daughters and sons after them.

Children, women, and men — but men in particular — were sometimes chained or yoked together whenever groups of slaves were moved from place to place before the end of the Civil War. Coffle was the name given to this group as it moved.

In the case of Goodwood Plantation, the coffle was driven here after their master Hardy Croom decided to move his interests and his young family from their home near New Bern, North Carolina. But first, he had to move his slaves to start building a grand house and preparing the land for cultivation.

Croom’s eyes were set on expanding his holdings into the promising cotton-growing farmland available near the new state capital after Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1819.

Throughout the South, coffles could be seen everywhere. Countless descriptions of them exist. Witnesses detailed coffles as a terrifying practice in which human beings were driven like mules to be sold or relocated for the labor they could provide.

One account from 1834 remembered a coffle encamped for the evening.

“Numerous fires were gleaming through the forest,” the witness wrote. “It was the bivouac of the gang. The female slaves were warming themselves. The children were asleep in some tents; and the males, in chains, were lying on the ground, in groups of about a dozen each.”

Nearby, “the white men … were standing about with whips in their hands.”

The movement of coffles was something repeated elsewhere as good farmland became available across the rest of northern Florida.

Not long ago Jim and I visited the antebellum Haile Homestead near Gainesville. Much the same story was repeated there as a white family named the Hailes moved in with their coffle of enslaved people from South Carolina, hoping to profit by extending the Cotton Kingdom into Florida.

It was yet another Trail of Tears.

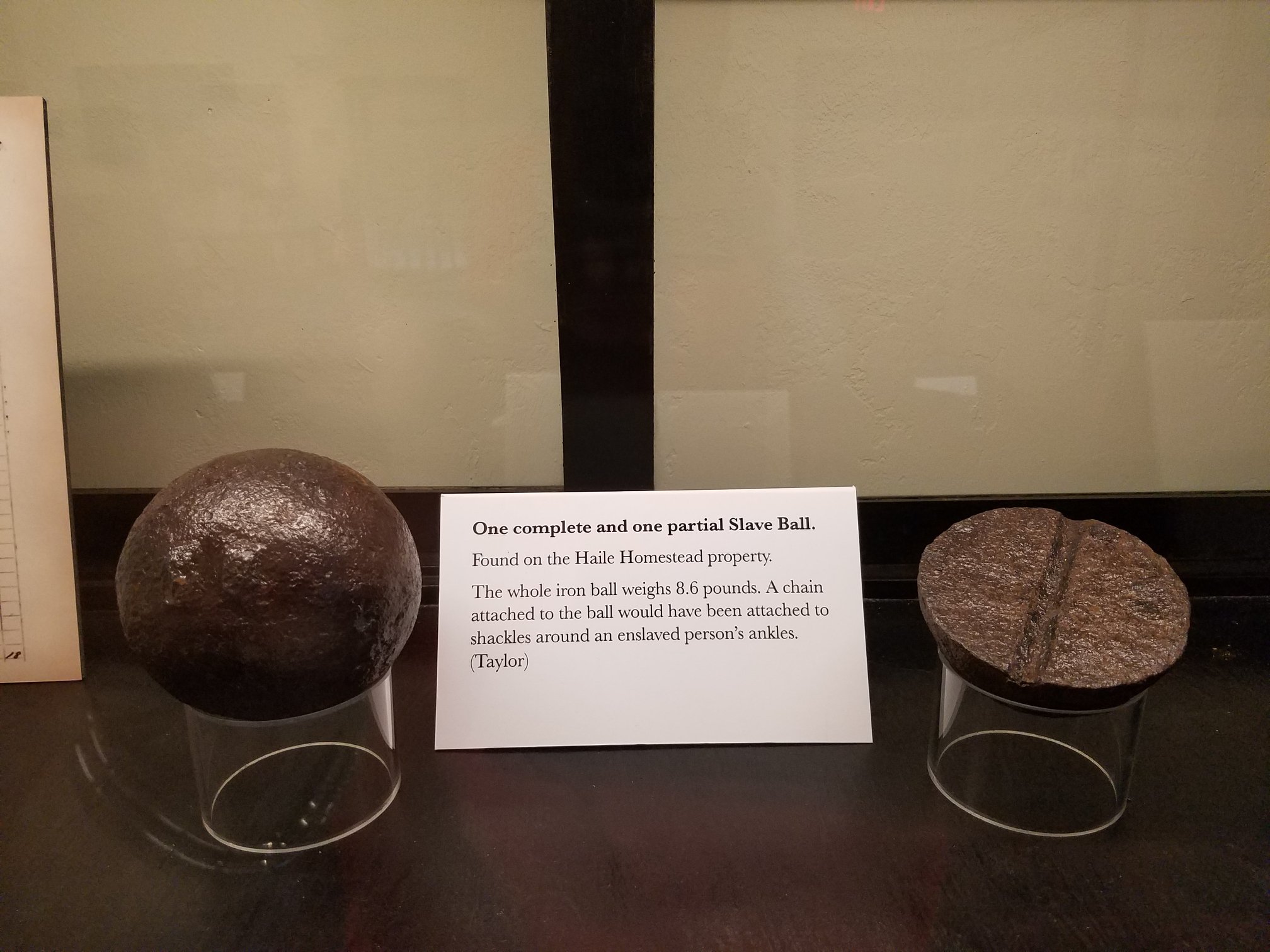

I was shocked at the Haile museum to see iron balls found in the yard there, only a few miles from today’s University of Florida. They were pieces of the infamous ball-and-chain hobbles used to stop enslaved people from escaping.

Until that point in time, I had never seen a real slave ball — and had never imagined seeing one found in a yard in the Sunshine State.

These stories from Gainesville and Tallahassee are part of a much larger story. Smithsonian Magazine has described the forced relocation of enslaved Americans before the Civil War as the largest and longest single migration of any group in the nation before 1900.

“The Slave Trail of Tears is the great missing migration — a thousand-mile-long river of people, all of them black, reaching from Virginia to Louisiana,” wrote Edward Ball in the article. “During the 50 years before the Civil War, about a million enslaved people moved from the Upper South — Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky — to the Deep South — Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama.”

Florida was only a small player in this much larger human tragedy. Yet there were many Trails of Tears that ended here.

Including at Goodwood Plantation.