Growing up a Southern child was an exercise in pretending that obvious pain did not exist. I was a thoughtful boy, as my teachers often said, with little talent for denial. So it was an exercise I failed.

Relatives at reunions refought the Civil War with such red-faced anguish that I sometimes fled to the chicken yard at my grandmother’s homestead to be with someone, anyone, even a flock of birds, that was not so angry.

This anger came from the pain of a conquered people. I knew this in my heart.

My people.

And conquered over what? — States rights? Federal overreach? Moonlight and magnolia?

None of the liturgical responses we were taught truly answered the question.

Nor did they fully explain the pain.

I often saw that pain in the faces of others — the stultified women who understood the damage better than most. The impoverished old folks living with their regrets. The aimless men injured by their own violence. And most of all the black men and women who became perpetual scapegoats for an anger that lingered in the air like the scent of some narcotic flower.

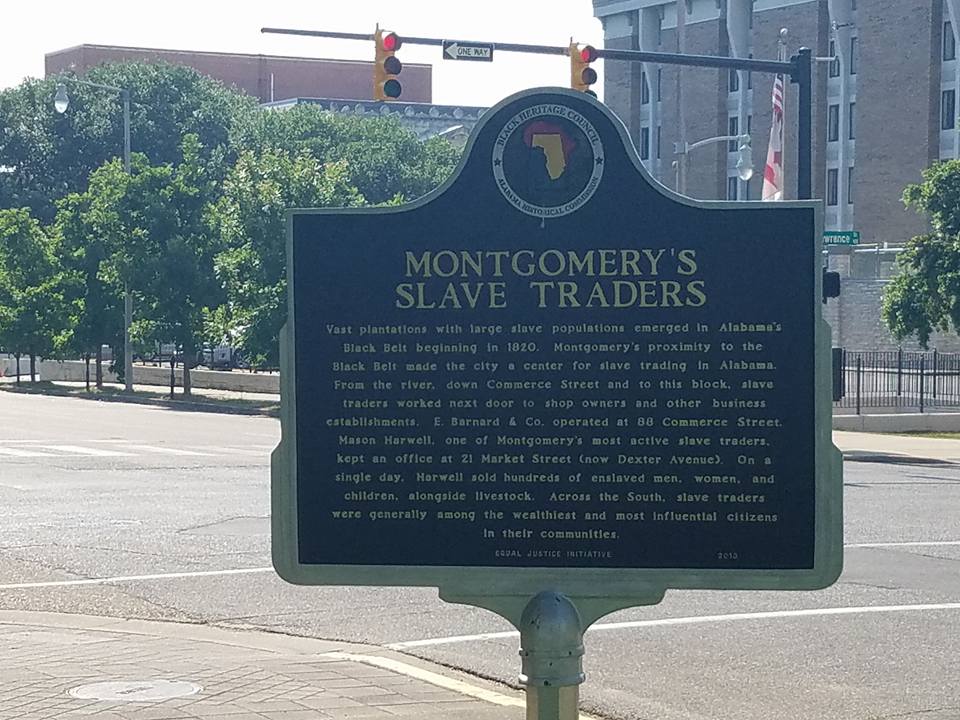

Slavery and its twin, Jim Crow, cast an appalling shadow over every aspect of life. Even my life, when it began in the 1950s.

And we Southern children were taught from the cradle a catechism of the Lost Cause. It was a Cause so noble, we children learned, that it brooked no criticism even as it hanged innocent people in trees.

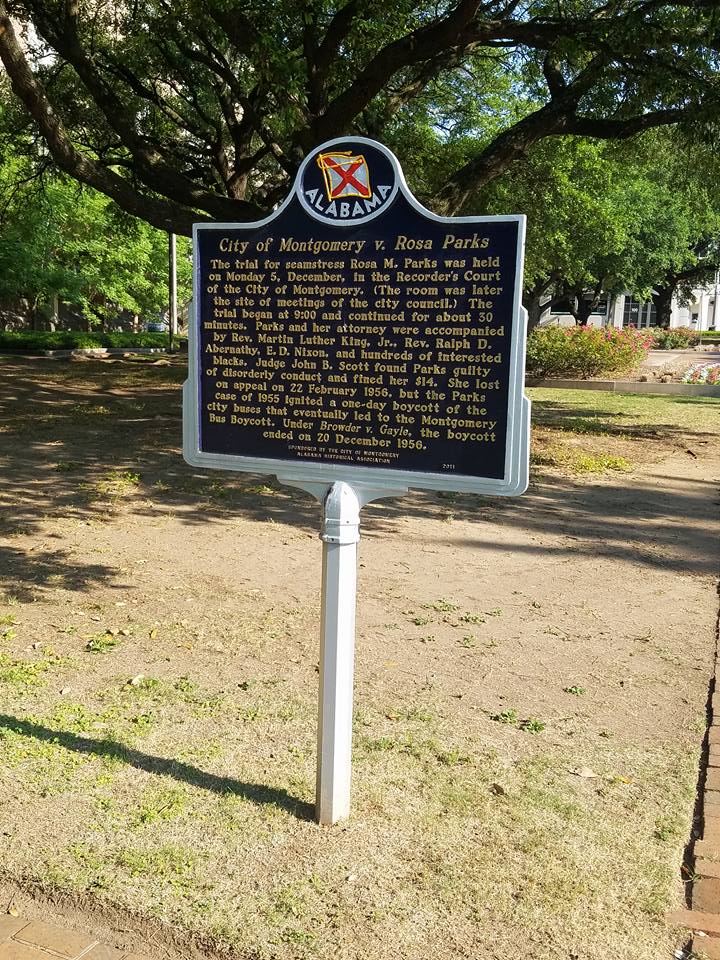

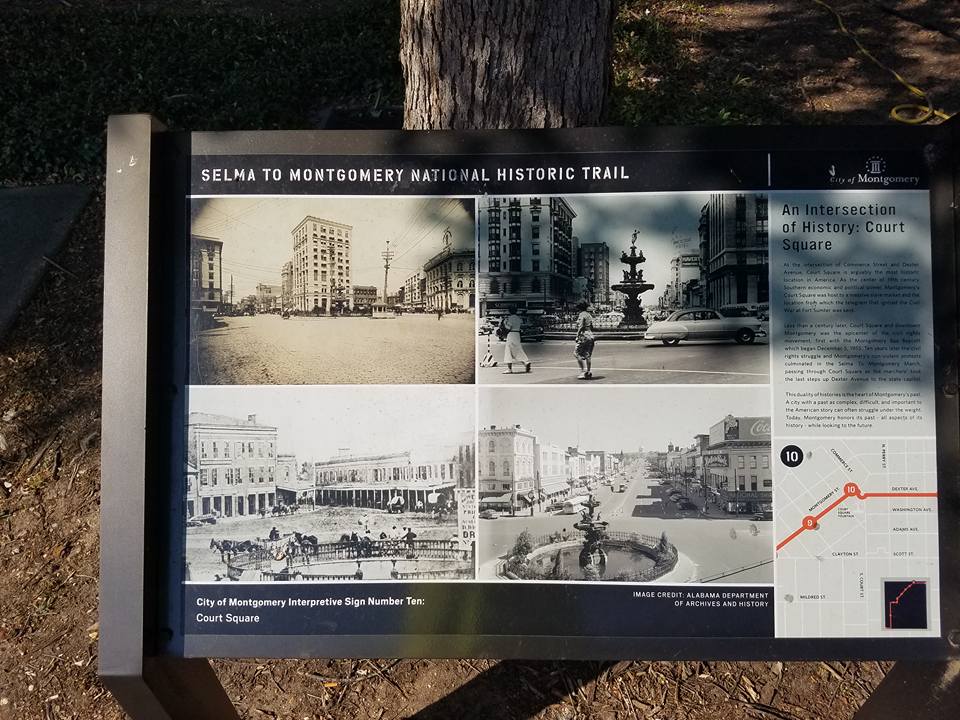

One reason Jim and I came to Montgomery was to get a closer look at how the South is still struggling with this pain. It is the subject of the new National Memorial for Peace & Justice a few blocks from where we are staying in downtown Montgomery.

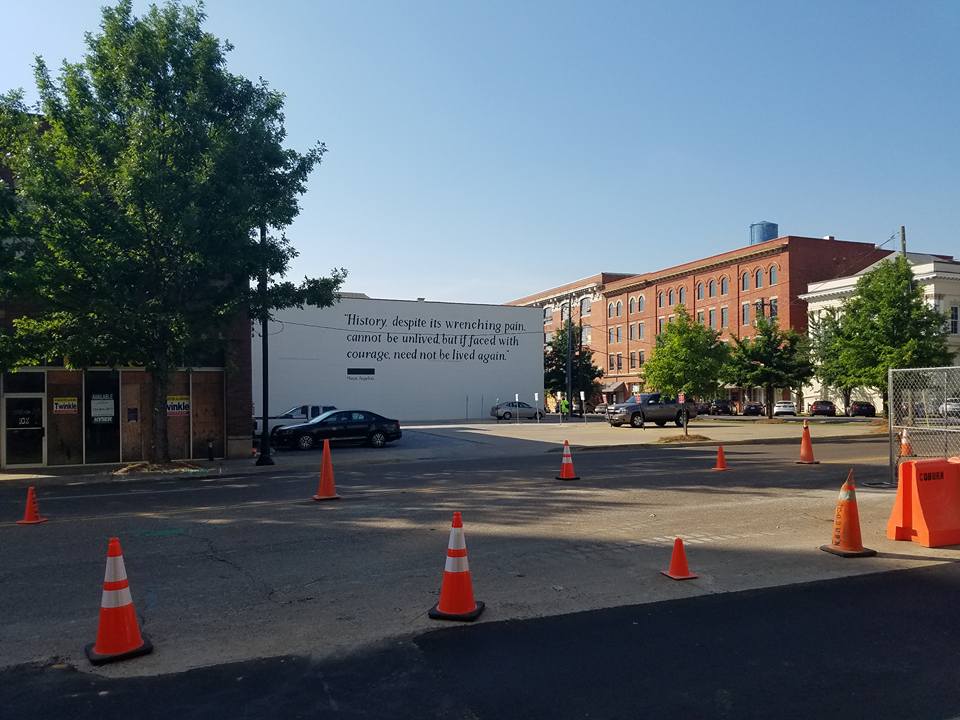

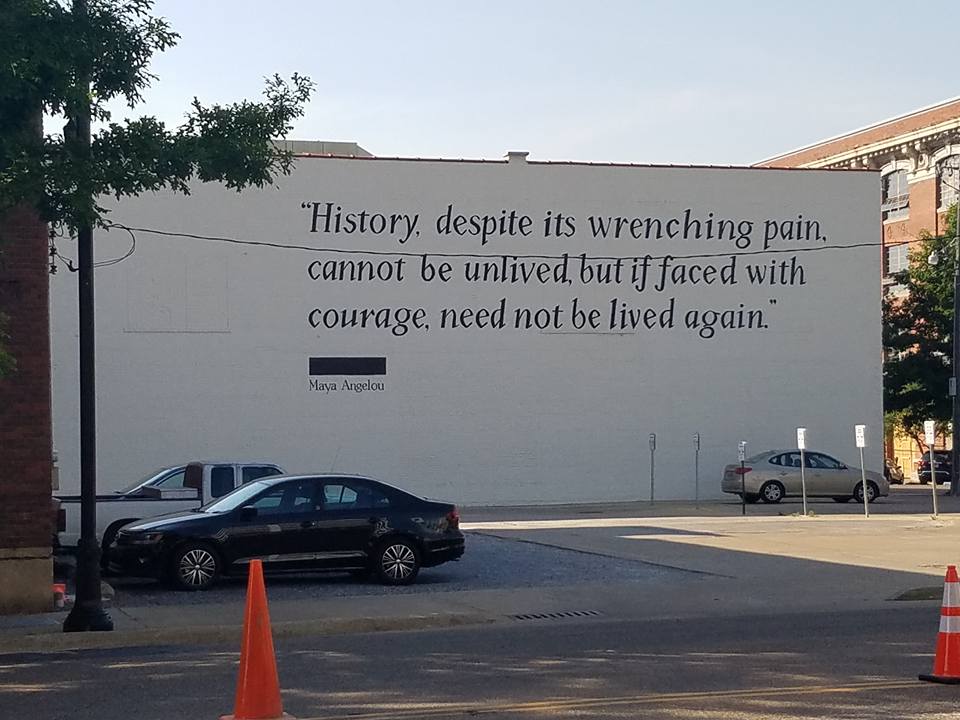

Walking near our hotel tonight, we saw the wall of a nearby building painted with a quotation from Maya Angelou that captures something about the endeavor.

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Faced with courage. Those are the important words. Cowardice only leads back to the failures of the past.